Lost in translation

| Date :01-Sep-2024 |

By Aasawari Shenolikar :

IN JESST

“Hi, can you give me a kilo of minced meat?” I asked the butcher. My son-in-law loves goat mutton, and in the USA, where he is currently stationed, goat mutton is a rare commodity. So whenever I go to Chicago, the first thing that we do - my son-in-law and I - is travel 25 miles to shop for goat mutton, so that he can have his fill, till my next visit. But that’s not the hard part - as I realised during my last visit. The real challenge is communicating in ‘English’. Yes, you read that right. I mean the language of Shakespeare, Dickens, and Rowling-but with a twist. It’s not just accents; it’s entire words that, quite simply, haven’t crossed the Atlantic well.

Last time when we visited, my son-in-law was travelling, and so it was left to me to procure the meat. Google came to my help, and I found that there was a small butcher shop, 4 miles away that sold goat mutton. So I picked up a jute bag, and walked to the shop. If the weather is perfect, which it usually is, in the month of October, I do not mind walking at all. On reaching the shop, run by Spaniards, I asked if they had goat mutton. That part he understood, and he nodded. My next question was if I could get a kilo of minced meat and a couple of kilos of ribs. Wide -eyed he stared at me, this time nodding his head from side to side. And then he shook his hand - the gesture clearly meant that he didn’t understand. I tried to explain, using sign language, speaking slowly and clearly for I thought he didn’t understand my accent, but to no avail. There was an Afro American customer hanging around, I turned to him and asked if he could help me out.

“Minced meat, a kilo,” I reiterated. He simply shrugged his shoulders and drawled, “Lady, I ain’t don’t understand whatcha saying.” How could I tell him that I couldn’t understand what he was saying - two negatives in a sentence- that’s now what Mrs Raghubir taught us in school. At this point, the people in the butcher shop were looking at me the way one looks at a crossword puzzle clue they’re certain doesn’t belong in the paper.

By this time I had pointed to a cut of mutton, and I was told that I had to buy the entire lot - he will not chop it into the weight that I required. It weighed 6 pounds, a little more than my requirement in kgs; I had no recourse but to agree. Mentally I calculated how many kilos, and then it suddenly dawned upon me why the butcher was unable to comprehend how much I wanted. He didn’t understand the ‘kilo’. The Americans measure in pounds, and have no clue about kilos. And at the same time it also struck that he probably didn’t understand what the word ‘minced’ meant. So I explained to him, the kind of mutton that is used in making burger patties, gesturing wildly with my hands all the time. “Ah!” he smiled, “you mean ground mutton.” I sighed - in relief. Mission accomplished.

This incident reiterated that we, Indians, are truly a smart race. If someone says pounds, we quickly convert it into kilos; if someone says miles, we calculate in kilometres. We don’t shake our heads in disbelief at the metric system being used - we quickly convert and calculate. Not just the educated lot, but also our dhobis, the vegetable vendor, the raddiwala. That’s how smart we are!

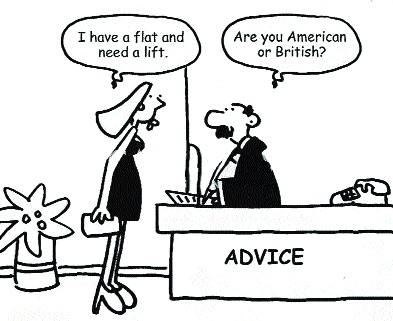

We Indians follow the British English; but America and Britain - are two nations divided by a common language. And because we are steeped in the Queen’s language, we have to, many a time, navigate a minefield of misunderstandings in Uncle Sam’s land. Simple everyday words suddenly become an alien language. And you start questioning your own credibility of knowing the English language.

“Bianca, please be careful on the footpath,” I cautioned my grandson’s nanny, as she was taking him to the park in his stroller (pram for us) and there was some construction activity going on on the footpath. She had a questioning look on her face. “A footpath is a small walking path, running parallel to the road, meant for pedestrians to walk,” I explained. She was still bewildered. “She means a sidewalk,” my daughter jutted in, grinning widely.

“Aah?” the relief in Bianca’s voice, for comprehending something as simple as a footpath, in American usage, was evident.

Then a couple of days later, I and my daughter went to LensCrafters to collect her spectacles. As we reached the outlet, she got a call, and she handed over the receipt to me, gesturing that I should go inside and pick them up. “Hi,” I was sprightly in my greeting ( you have to be for American are a raucous lot when it comes to greetings), handing over the receipt. “Are the spectacles ready?”

“Sorry,” the girl behind the counter responded. “I’ve come to pick the pair of spectacles,” gesturing to the array on the shelf. “Oh, you mean glasses,” she stated. Now this was problematic for a reason, which I laid out in front of my daughter. “When you mutter glasses, I instinctively picture a nice set of drinking glasses, the kind you’d use for a cocktail or drinking sherbet,” I stated. “That’s why Americans are more specific - it’s not just glasses, it’s eyeglasses,” she said. I could only roll my eyes at the absurdity of it. Would the users of glasses be using them in any place else other than placing them on the eyes?

The most frequent showdown, though, happens over my insistence on using the metric system. I still cannot get over the sheer look of horror when I asked for a “kilo of minced meat” at that butcher’s counter ( as mentioned earlier). I swear I saw the life drain from the poor man’s face. Later, while introspecting, it dawned that the word ‘mince’, in the USA, is reserved for things like minced garlic or minced onions. But minced meat? You’d think I had asked for a culinary masterpiece involving sugar and spice and something nice, like their mince pie - a dessert filled with fruits and spices.

Hello! Where’s the meat in your mince pie?

And what’s wrong with using ‘kilo’? The metric system makes so much more sense. Yet, Americans persist in using ‘pounds’, ‘ounces,’ and ‘miles.’ It’s as if they have a personal vendetta against anything divisible by 10.

Of course, this language barrier doesn’t stop at the butcher’s counter. It carries over into daily life. “Ma’am the elevator is out of order,” the footman cautioned. “Oh man, now I’ll have to walk up a flight of stairs,” I responded. “You’ll have to climb the steps,” he iterated. “That’s what I said, walk a flight of stairs,” I stood my ground, but ultimately shrugged and climbed the steps.

The list of words getting lost in translation is endless. They don’t ‘queue up,’ they form a ‘line.’ Boot of the car is trunk, biscuit is definitely not what we have at tea time. Try saying, in times of emergency, “Call nine double one,” and chances are that help will never arrive. For they do not understand the concept of ‘double one’ or triple nine’. It has to be ‘nine one one’ (911 - try paying attention when watching any crime series on the OTT and you will notice it). If I say I stay in Apartment ‘triple five nine’, it will not register.

It has to be “I stay at five five five nine.”

Sometimes I argue, cannot persist for after a time it’s like beating your head against a wall, many a time I just let it go. For I know that the quirky idiosyncrasies of the English language can be truly entertaining. Tomato (tomayto) or tomato (tomahto) - who cares?

So, whether it’s a ‘kilo of minced meat’ or just a ‘queue’ at the supermarket, let’s continue to revel in the wonderful confusion that ensues. For it provides all of us with fodder for laughter.

Oscar Wilde was spot on when he stated, “We have everything in common with America nowadays, except, of course language.”