KILL OR PRESERVE?

22 Sep 2024 16:35:13

■ By UTTARA GANGOPADHYAYA :

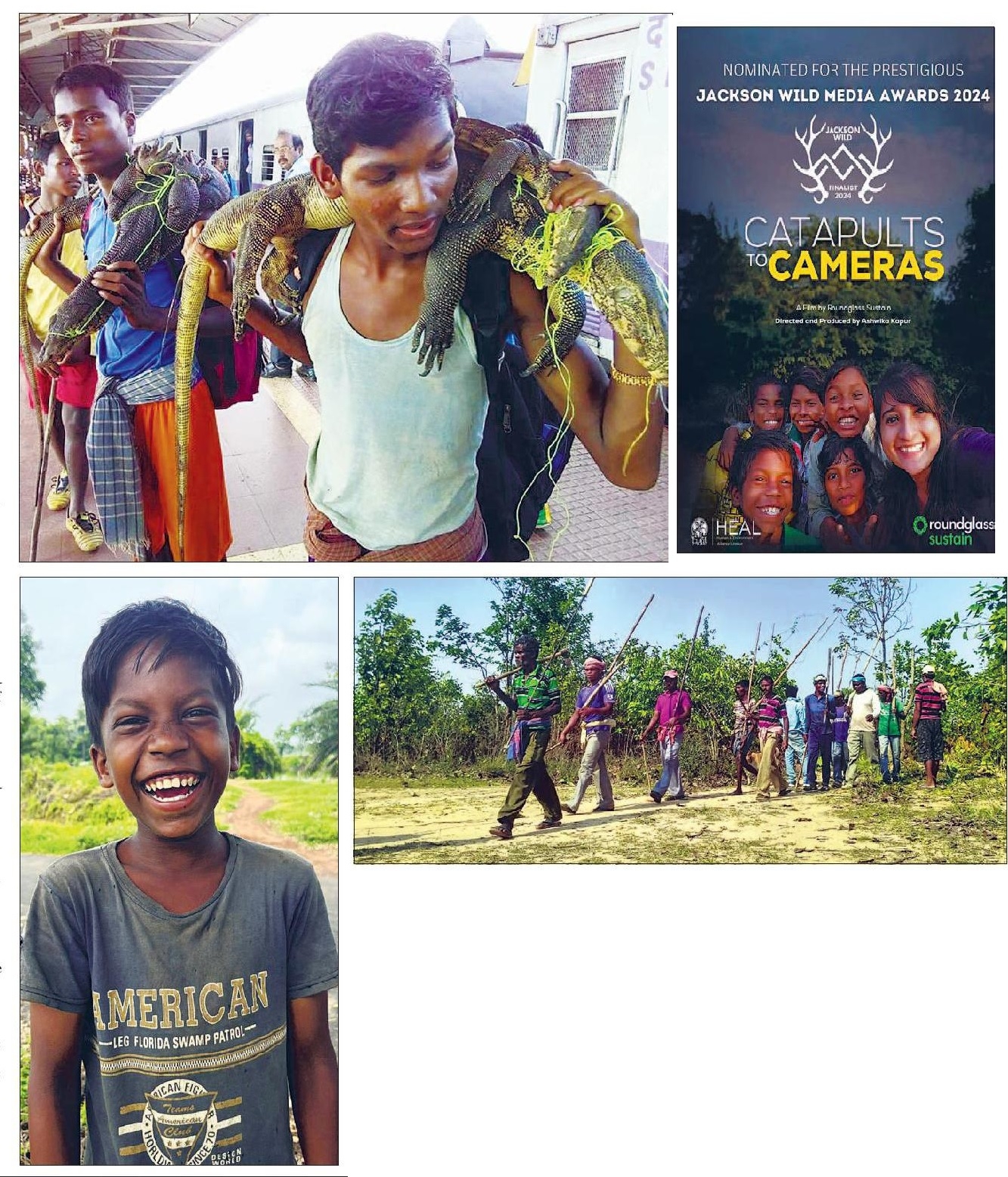

Catapults To Cameras directed by wildlife photographer and conservationist, Ashwika Kapur, has made it to the shortlist of the Jackson Wild Media Awards, considered as ‘Nature film’s equivalent to the Oscars.’

Catapults To Cameras, a 40 minute film produced by Roundglass Sustain (a philanthropic education platform) is making

waves documenting the transformation of

five boys – aged 7 to 10 years, who were

persuaded to exchange their slings or catapults

(used for hunting birds and small animals) for cameras to photograph animals in their wild habitats.

The real life success story is from Jhargram, a district in the southern West Bengal, says Meghna

Banerjee, co-founder and executive director of

Human and Environment League (HEAL), Kolkata,

where Kapur is an advisory member and is working

to stop the massacre of animals in the name of ritual hunting.

It was June 2016.

Banerjee and her team members had rushed to a

railway station in Purba Medinipur district of West

Bengal as a local volunteer informed them that

groups of armed hunters were on the move, travelling by trains. They were shocked at the sight that

greeted them.

The railway platforms were littered

with carcasses of animals – snakes, monitor lizards,

civets, wild boars, deer, birds, to name a few. “It was

a gut wrenching sight,” recalls Banerjee.

The hunters were moving around openly with

their weapons, skinning the animals, cooking the

meat as if it was a picnic. Although hunting and

trading in over 1800 species of wildlife or their

derivatives have been banned in India since the

implementation of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972

(with a few later amendments), HEAL members

realised there was no government official – from the

forest department or the local police – present, to

take stock of the situation, apprehend the hunters,

or confiscate the dead animals.

It was one of the many incidents of purported ritual hunting that HEAL members came across in the

next few years. As part of their three-pronged

approach – species conservation, habitat protection,

and mitigating human-wildlife conflict –HEAL

works on a wide range of issues.

One of their major initiatives under species conservation is ‘bringing an end to the large-scale killing of

protected wildlife that happens every year, over several days, under the garb of tradition and culture’.

Ritual hunting –‘shikar utsav’ as it is popularly

known, is thought to be a part of tribal culture and

therefore cannot be interfered with. However,

Banerjee says, there has been no such exception provided in the legal framework.

In many cases, HEAL found that the hunts were

recreational in nature in the guise of ritualistic

hunts. One of the biggest hunts takes place sometime in June, for nearly five days, around the festival

of Phalaharini Kali Puja. There are about 50 days in

a year when such hunts are organised.

In many instances, they found local hunters were

joined by those from neighbouring states of

Jharkhand and Odisha. “It may not be part of their

(hunters from non-tribal communities) tradition but

they sort of pile on. When they see a group of people

going on these hunts, they know it’s for exotic meat

and don’t let go of the opportunity,” Banerjee says.

It is not an easy task to go against the grain and

involves risks. The group has been mobbed, their

cars surrounded by agitating hunters, their cameras

broken. Beginning with Howrah and Purba

Medinipur districts, HEAL’s surveys expanded across

the districts of Jhargram, Paschim Medinipur,

Bankura, and Purulia.

The annual ritual hunting festivals pose significant threats to wildlife, including protected species.

Often skins of animals such as monitor lizards are

preserved because they have commercial value.

In the initial years of their study, members of

HEAL found that the forest department, the police or

the local administration, or even the railway authorities did not take any cognizance of the illegal activities that were taking place under the guise of ritual

hunting. In 2016 and 2017, HEAL documented

mostly the train driven hunts, gathering extensive

information about the hunters and did photo- documentation. The group approached the law enforcement organisations but nothing worked out.

Subsequently, HEAL filed two Public Interest

Litigations (PILs) in the Calcutta High Court (CHC)

seeking orders on the forest department and district

administrations to end this annual massacre of

wildlife. In response to their petitions, the CHC

passed orders in May 2018 and April 2019, disallowing all hunting activities in the garb of ‘rituals,’

Banerjee informs.

The Court also directed the West Bengal state

authorities and the railways to take all possible steps

to prevent the ritual hunting of wildlife in the said

districts

The bench also proposed the formation of a panel

– the Humane Committee – for the five districts

involved. But only a legal approach is not enough to

stop recreational hunting, HEAL felt. It is also necessary to earn the trust of the local people and make

them aware about the negative impacts of hunting.

“During our surveys, much to our regret, we often

noticed that small boys were also being taken along

for the hunts by their elders. Getting exposed to such

brutal hunting at such an early age - how are they

going to grow up and perceive hunting - a crime at

the end of the day - worries all of us.”

Led by Kapur, who would often visit these villages

for photo documentation, HEAL began to reach out

to the kids in a particular village in Jhargram (often

considered the epicentre of hunts).

Based on their interactions and suggestions from

the local teams, they short-listed five boys. Hunts

are, by the way, exclusively a male domain.

“These kids were extremely good shots with their

slings. We gave them cameras and some basic training. Ashika and the HEAL team went out to the field,

started taking their own pictures, and then the

change happened.” According to Banerjee, the team noticed the kids’

hunting instinct changing after photographing birds

in the fields and seeing the beauty of nature from a

close range. The boys not only stopped hunting but

began to convince their elders to refrain from it too.

The photographs were displayed at an exhibition

in the village and garnered a lot of attention. From

looking at the animals as a quarry or a prey, they

began to see them as living things which should be

protected.

Banerjee hopes that these boys will be an inspiration to other kids too.

Through their ‘Zero Hunting Alliance’, HEAL aims

to ‘bring together volunteers from other environmental organisations and concerned citizens under

a single umbrella group dedicated to eliminating

ritual hunting’.

Although recreational hunting may not have

stopped altogether, there has been a significant

decline in numbers, says Banerjee. Members of

HEAL remain hopeful that with legal backing, trust

building programmes, and awareness campaigns,

they will win the support of the local villagers, who

in turn would ensure that hunting does not take

place in their areas. (Photo courtesy HEAL)

(TWF) ■